For Taylor Wilson, Medicaid isn't just a program; it's a lifeline

"Oliver doesn’t get a shot at life if we don’t get him the care he needs. Rare diseases are not collectively rare. Almost everyone knows someone with a rare disease or who has a kid with a rare disease.”

Taylor Wilson fills a syringe the size of a giant turkey baster with a complex mixture of sodium bicarbonate, levocarnatine, K tablets for potassium, formula, a high-calorie powder called Duocal and an acid block and inserts it into Oliver’s feeding tube below his belly button.

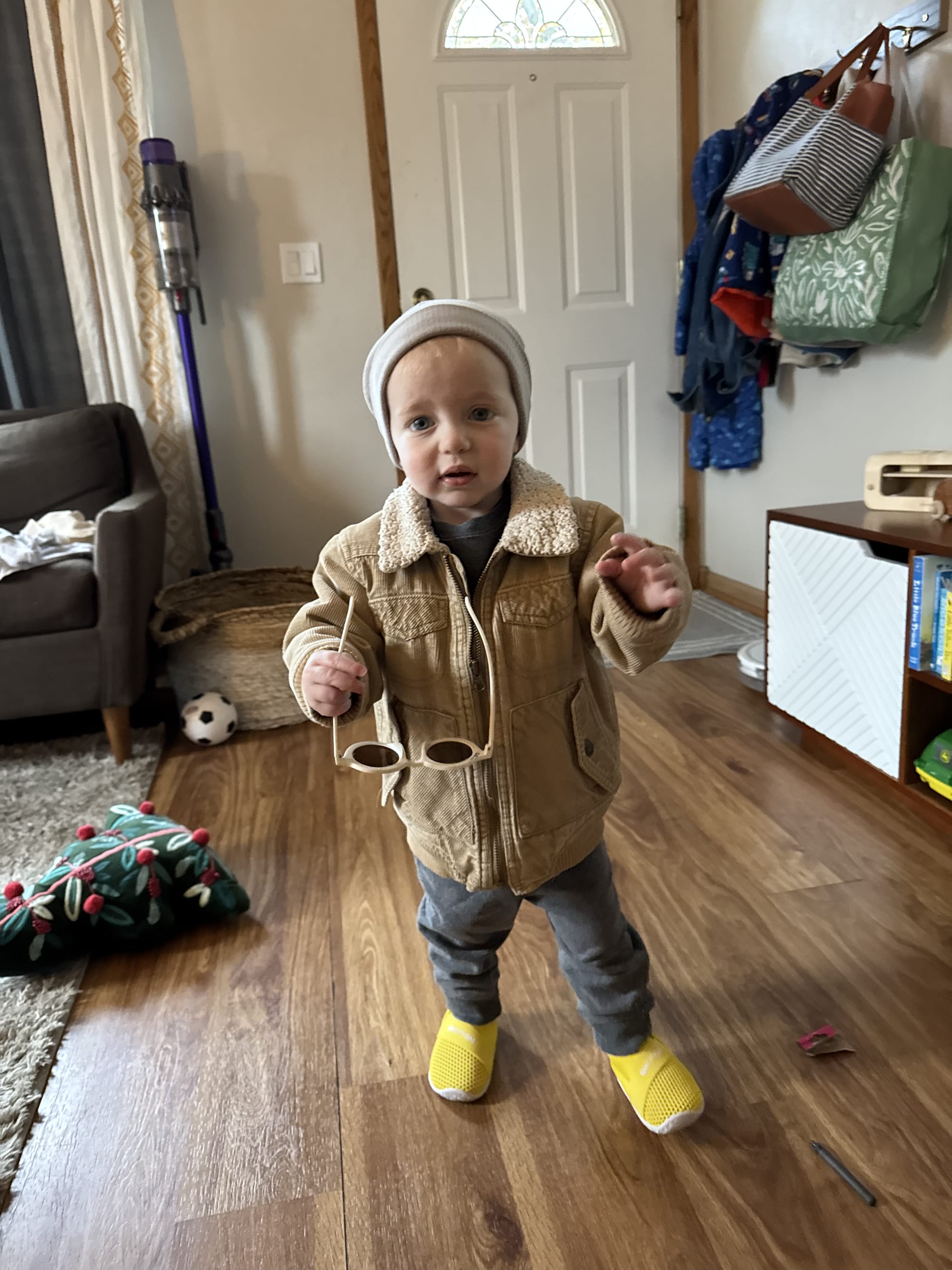

The life-sustaining ingredients enter directly into little Oliver’s stomach, providing him the nutrition and calories he is unable to take in orally. Mom empties four syringes into her 23-month old son’s belly. By the third syringe, Oliver, a frisky little boy with a shy but winning smile and big gray-blue eyes, is starting to belch and though he takes the final offering, he’s not particularly happy about it.

While Oliver doesn’t puke after this feeding – one of five Taylor must administer during the day – he often does.

“Sometimes it makes him gag,” Taylor says. “It’s just kind of a big liquid volume going in all at once.”

Oliver is still learning to accept food orally due to a buildup of cystine crystals in his muscles that leads to, among other things, muscle weakness and a swallowing dysfunction.

It is one of the many complications resulting from an almost unimaginably rare disease called Nephropathic Cystinosis, a metabolic disorder characterized by the accumulation of cystine in various organs, most critically, the kidneys. It affects only 2,000 people worldwide. That, and the fact that the drugs and other therapies needed to sustain a child to maturity are so expensive – the life expectancy with the proper treatment has gone from 10 years to 57 years – make it something no private insurance will take a second look at. Indeed, most insurance companies have never even heard of the primary drug used to combat the disease.

Taylor was floored when she saw the bill for that drug – Procysbi – the essential treatment that slows the progress of Oliver’s disease and allows him to, if not exactly thrive, then at least survive through his early years. Ultimately sufferers of Nephropathic Cystinosis require multiple kidney transplants throughout their life, likely starting in their late teens.

The bill for that first dose of Procysbi? $69,000 a month. That has since gone up as doctors adjust the dosage to meet the increased mass in Oliver’s body as he grows. It is the largest, but hardly the only, enormous expense that, without insurance, would be impossible for Taylor to afford.

“I mean, it’s not like I can get another job or not get a cup of Starbucks and be able to afford any of this,” she says.

And it’s just one of the many costs of raising a child with Nephropathic Cystinosis, though easily the most expensive.

‘A Sinking Feeling’

Taylor knew something wasn’t right with Oliver at around eight months. He would put food in his mouth but not swallow it and then began the digestion problems. The real scare came when he began to fall off the growth chart after being in the 97th percentile for his age. Trips to Milwaukee Children’s Hospital and test after test yielded nothing but some frightening speculation and unbearable weeks of waiting.

When the answer finally came back – that Oliver suffered from a disease that occurs in just .0000003 percent of the world’s population – she was relieved that it wasn’t one of the terminal illnesses that had been mentioned. Then the questions came. Could something so rare have a support system? What all is involved in his treatments? How much will it all cost? How can I possibly afford that?

The answers to those questions have left Taylor feeling grateful, but since the November elections, nervous as well. First, Oliver can thrive as a person well beyond middle age. Second, there actually is a support group of parents who have helped sustain her emotionally. The doctors and caretakers have been a godsend and the guidance they have provided has allowed Taylor and Oliver to live high-functioning, if demanding, lives that revolve around a schedule of feedings, drugs, lots of laundry, lots of therapy and essential treatments.

And thanks to Medicaid, the government program for people, like Taylor, who couldn’t possibly afford the regimen of care required and whom private insurance won’t touch, the matter of cost has been taken off the table.

“For some diseases we just don’t have the scientific advances yet,” says Taylor, who works from home as a graphic designer. “But we do have the advances to help Oliver. We have the time. We have the resources. We have the people who want to help him. We have the medications.

“But we don’t have access to any of that if we don’t have Medicaid. And that’s not catastrophizing. That’s not exaggerating. I’ve seen those six-figure bills show up. A bill that’s bigger than your entire yearly salary. That’s a sinking feeling that’s out of everybody’s control.”

Medicaid covers not just that expensive drug but almost every aspect of Oliver’s extensive regimen of care.

“I think people look at Medicaid a little side-eyed,” Taylor says. “People who I don’t think really understand the true depth of this, who think, why am I paying for your kid to get millions of dollars of stuff my kid doesn’t get.

“And I can sort of empathize with that,” she adds. “But the truth is, Oliver doesn’t get a shot at life if we don’t get him the care he needs. Rare diseases are not collectively rare. Almost everyone knows someone with a rare disease or who has a kid with a rare disease.”

That’s why when Taylor first started hearing about Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s blueprint for gutting so much government spending, including crucially, Medicaid, she began to panic. While candidate Donald Trump tried to distance himself from Project 2025 on the campaign trail he has since adopted nearly all of its draconian planks, including cutting Medicaid by nearly $2 trillion. There is talk about putting a lifetime cap per person.

“And I mean, how much is that?” she asks. “How much is Oliver’s life worth? It’s scary, ominous and open-ended language.”

“I get the sense that Trump and his people are indifferent to people like Oliver,” she continues. “I get the sense that they lack of regard for real human life or it doesn’t even occur to them, that it’s not even on their radar. It seems to me like if it wouldn’t affect them, they don’t care. And that is going to cost lives. So if those are the kinds of people you want representing you, people like Oliver are going to suffer.”

‘I want him to have that chance’

Taylor also raves about the administrators that helped walk her through the Medicaid process that, already overwhelmed with her new reality, she felt almost helpless to navigate. These are the people, she says, who are the backbone of a functioning government but who often get scapegoated as unnecessary, faceless bureaucrats. There have been ongoing massive cuts to civil servants since Trump took office.

Taylor has had little luck getting through to first-term Congressman Tony Wied, from whom she received as a response to her plea to support Medicaid, a fairly proforma email that seemed to place a lot of its emphasis on inefficiency and not essential need, which she found disappointing.

“I am committed to exploring policies that will benefit the 8th District while also ensuring that taxpayer dollars are spent efficiently and effectively,” it reads in part.

She has had much better luck and, to her mind, more understanding responses from Sen. Tammy Baldwin and State Rep. Lee Snodgrass, both strong proponents of protecting and strengthening Medicaid. By not expanding Medicaid qualifications in the state, Wisconsin is annually surrendering a billion federal dollars.

For Taylor, Medicaid is not a bloated, faceless bureaucracy but something that gives her and Oliver a chance at a happy, fulfilling life. “Medicaid isn’t just a program,” she says. “It’s a lifeline for kids like Oliver. I talk to lawyers from insurance companies, people who don’t know anything about disease, who don’t have a medical degree, who are questioning you about this and about that. They only care about the bottom line."

“But who could meet Oliver and say, you know, that’s too expensive? Well, you’re right, it’s pretty expensive but we’re going to do it. We have to. Because that’s what we’re up against. That’s why Medicaid is so deeply important to society."

“So, yeah, Oliver isn’t going to get better. There is no better. There’s just a life that he can live and I want him to have that chance.”

For Taylor Wilson, Medicaid isn't just a program; it's a lifeline © 2025 by Kelly Fenton is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0